Police officers indicted more often, but seldom convicted after shootings

More police officers in Texas are being charged after questionable shootings, but prosecutors who were able to convince grand juries to indict have been less successful at securing convictions at trial, reported Tasha Tsiaperas the Dallas Morning News (who has a really cool, bond-villain-type name!). In related news, Grits contributing writer Eva Ruth Moravec had a feature in the Houston Chronicle about a Freeport police officer acquitted by a Brazoria County jury for shooting his unarmed neighbor in the next apartment. It was as negligent a situation as one could imagine, so maybe civil court is still an option: The cop apparently slept with a loaded gun in his bed (and in this case, his finger on the trigger, safety off) and fired it through his headboard into the next door apartment. Attn: Texas Monthly, this is mandatory Bum Steer material.

Police unions, the media, and me

Most local media coverage of the Austin police contract has been dismissive of the push by the Austin Justice Coalition and their growing list of allies to get the city council to vote "no." This, despite opposition to the contract from hundreds of signators, more than a dozen groups, and even though, in a staunchly Democratic county, D precinct chairs unanimously voted for a resolution urging city council to kill the deal. Currently the vote is scheduled for December 14th. At the Texas Observer, Michael Barajas has a feature explaining more fully "How the expiration of Austin's police union contract could be a rare opportunity for reform." Former CLEAT mugwump and long-time police-union leader Ron DeLord, who was lead negotiator for the Austin Police Association on the contract, complained on Twitter that Barajas didn't talk to him. So I suggested DeLord do a podcast interview to air his views, and he agreed(!). I hope y'all are looking forward to that as much as I am. Mainly I want to talk to him about his books: See Grits' discussion of his latest one, and also the opening segment of our August Reasonably Suspicious podcast discussing his remarkably accurate prediction of Texas' police-pension crisis, which was a contentious legislative imbroglio this year resulting in outcomes with which no one is happy, but which brokered an uneasy, temporary truce among the parties. If the economy holds.

Evaluating police bodycams

Coupla items here: A new study found bodycams reduced use of force episodes at the Las Vegas PD while providing quality evidence that supported criminal convictions mostly of defendants, not cops. But many advocates, your correspondent included, believe the laws limiting transparency around footage reduce the accountability benefits. Supporting that claim, Nick Selby wrote on The Crime Report that, "In October of this year, the biggest-ever randomized study of body cameras showed no measurable reduction in complaints or use of force by officers in Washington, D.C." So the jury's still out on whether this will turn out to be an important accountability measure, as they were originally pitched in the hyped aftermath of the Ferguson protests.

With shortfall looming, a way to reduce DPS crime-lab volume

Plano PD is testing a device that can tell whether DNA exists on a piece of evidence before they send it to the lab instead of after. If this works as advertised, Governor Greg Abbott, his grants division, and DPS crime-lab folk should take heed. It might even be worth the Governor considering emergency grants to buy these for the biggest users of DPS DNA lab services to reduce the volume of cases. A lot of material sent has no DNA on it at all, and to screen that out up front would make a big difference on volume in a biennium when the Legislature told DPS to collect fees for part of their budget and the Governor has stopped them from doing it. That creates a shortfall unless they can find ways to reduce volume. This could be an important one.

Death penalty now mainly an LWOP plea-bargain chip

Texas will perform no more executions this year after the Court of Criminal Appeals issued a stay and halted Juan Castillo's planned trip to the death chamber. But expect life without parole sentences to keep stacking up as Christmas approaches. In 2016, according to the Texas Office of Court Administration, just three new death sentences were secured by Texas prosecutors, compared to 64 LWOP sentences. (A whopping 426 total capital cases were filed statewide last year, which was a ten percent increase from the year before, so many are called, but few are chosen.) These days, the death penalty is mostly a threat to get people to accept life without parole sentences in a plea bargain.

Harris judges sabotaging pretrial release order from feds

Harris County judges are sabotaging the pretrial release system mandated under a federal court order by refusing to release thousands of defendants who qualify, according to a report by the Texas Tribune (which doesn't use such strong language but supplies all the relevant details). Instead, the Sheriff has to release them outside of the purview of the Pretrial Services system, where they predictably have higher no-show rates. (One of the most important things pretrial services does to get them there are reminder calls and texts.) The key problem:

Defendants who are ordered for no-cost release by a judge or magistrate are entered into the county’s Pretrial Services department, which works to ensure those out on personal bonds know the date of their next court appearance and can provide additional conditions like drug testing, mental health services or GPS ankle bracelets. Those released by the sheriff aren’t monitored once they leave the jail.On judges as gatekeepers, redux

Here's a law review article by Stephanie Damon-Moore on a question Grits has thought about a lot: "why trial judges, who have an independent obligation to screen expert testimony presented in their courts, would routinely admit evidence devoid of scientific integrity."

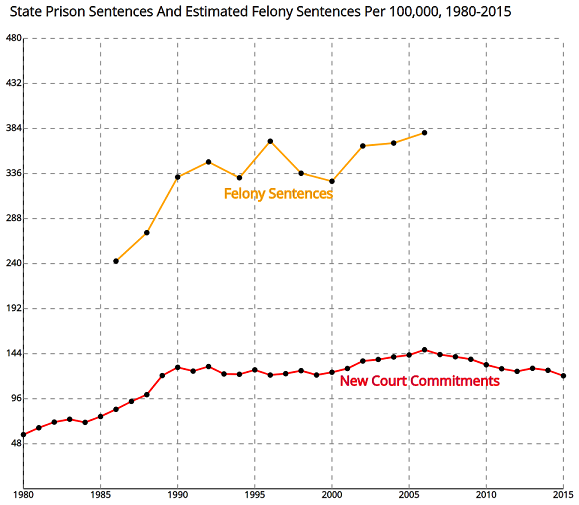

We've established that the War on Drugs contributed more to mass incarceration than critics like John Pfaff have claimed. But now the statistician who best proved that has come out with a new analysis demonstrating even deeper, more insidious aspects to the drug war's role. Compared to new prison sentences, which themselves skyrocketed, the number of total felony sentences (including probation, deferred adjudication, etc.) went up even faster! See here, and check out the whole analysis:

.jpg)